Chinese Medicine Yields Secrets: Atomic Mechanism of Two-Headed Molecule Derived from Chang Shan, a Traditional Chinese Herb

The mysterious inner workings of Chang Shan -- a Chinese herbal medicine used for thousands of years to treat fevers associated with malaria -- have been uncovered thanks to a high-resolution structure solved at The Scripps Research Institute (TSRI).

|

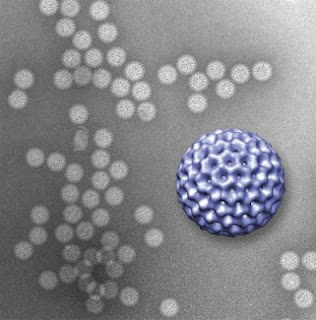

| Scripps Research Institute scientists have determined a molecular structure that helps explain how the Chinese herbal medicine Chang Shan works. (Credit: Image courtesy of the Schimmel lab.) |

The new structure shows that, like a wrench in the works, halofuginone jams the gears of a molecular machine that carries out "aminoacylation," a crucial biological process that allows organisms to synthesize the proteins they need to live. Chang Shan, also known as Dichroa febrifuga Lour, probably helps with malarial fevers because traces of a halofuginone-like chemical in the herb interfere with this same process in malaria parasites, killing them in an infected person's bloodstream.

"Our new results solved a mystery that has puzzled people about the mechanism of action of a medicine that has been used to treat fever from a malaria infection going back probably 2,000 years or more," said Paul Schimmel, PhD, the Ernest and Jean Hahn Professor and Chair of Molecular Biology and Chemistry and member of The Skaggs Institute for Chemical Biology at TSRI. Schimmel led the research with TSRI postdoctoral fellow Huihao Zhou, PhD.

Halofuginone has been in clinical trials for cancer, but the high-resolution picture of the molecule suggests it has a modularity that would make it useful as a template to create new drugs for numerous other diseases.

The Process of Aminoacylation and its Importance to Life

Aminoacylation is a crucial step in the synthesis of proteins, the end products of gene expression. When genes are expressed, their DNA sequence is first read and transcribed into RNA, a similar molecule. The RNA is then translated into proteins, which are chemically very different from DNA and RNA but are composed of chains of amino acid molecules strung together in the order called for in the DNA.

Necessary for this translation process are a set of molecules known as transfer RNAs (tRNAs), which shuttle amino acids to the growing protein chain where they are added like pearls on a string. But before the tRNAs can move the pearls in place, they must first grab hold of them.

Aminoacylation is the biological process whereby the amino acid's pearls are attached to these tRNA shuttles. A class of enzymes known as aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases is responsible for attaching the amino acids to the tRNAs, and Schimmel and his colleagues have been examining the molecular details of this process for years. Their work has given scientists insight into everything from early evolution to possible targets for future drug development.

Over time what has emerged as the picture of this process basically involves three molecular players: a tRNA, an amino acid and the aminoacyl-tRNA synthetase enzyme that brings them together. A fourth molecule called ATP is a microscopic form of fuel that gets consumed in the process.

The new work shows that halofuginone gets its potency by interfering with the tRNA synthetase enzyme that attaches the amino acid proline to the appropriate tRNA. It does this by blocking the active site of the enzyme where both the tRNA and the amino acid come together, with each half of the halofuginone blocking one side or the other.

Interestingly, said Schimmel, ATP is also needed for the halofuginone to bind. Nothing like that has ever been seen in biochemistry before.

"This is a remarkable example where a substrate of an enzyme (ATP) captures an inhibitor of the same enzyme, so that you have an enzyme-substrate-inhibitor complex," said Schimmel.

The article, "ATP-Directed Capture of Bioactive Herbal-Based Medicine on Human tRNA Synthetase," by Huihao Zhou, Litao Sun, Xiang-Lei Yang and Paul Schimmel was published in the journal Nature on Dec. 23, 2012.

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health through grants #GM15539, #23562 and #88278 and by a fellowship from the National Foundation for Cancer Research.